“Time is the single most precious commodity in the universe”

If I could be a fly on the wall for the pitch meeting for Jupiter Ascending where multiple studio execs are hypnotized by a headshot of Channing Tatum and the idea of another “sci-fi blockbuster.” The sisters have got to be the most engaging and eloquent pitch-makers in the field as they take giant budgets and produce idiosyncratic mainstream films that baffle the studios fronting the bill. Over and over again, these films relatively to out-right “bomb,” get panned by the general public, and we start the news cycle all over again. Budget and profit hang wringing by news sites and “social media critics” has only grown in the ten years since this film, becoming the first signicator in overall film success. I imagine when this came out, people all over the internet were hypothesizing that the Wachowskis would never get a budget of this size again, which was probably said for Cloud Atlas… and Speed Racer. As we got to the 2020s, the “original story” aspect was the anchor most easily recognizable to major studios. It was not until Lana returned to their beloved franchise that she was able to do it all over again. If their point was not made clearly enough in all of their films, Matrix Resurrections is their most obvious critique on their battle of art and commerce, tackling Hollywood’s newest obsession – the legacy sequel. Again, let’s put the pieces together: huge budget, nobody liked it.

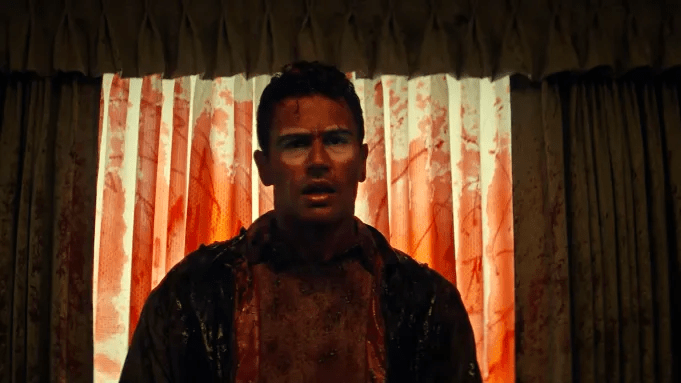

This is not meant to explain the unrepeatable careers of two of our great filmmakers, but to celebrate their most critically panned film. Jupiter Ascending is an earnest, interstellar adventure where you could be the most important character in the universe, as long as you want to. Jupiter Jones (Mila Kunis) works for her families house cleaning business, scrubbing toilets and fantasizing about a life of affluence. After witnessing the attempted abduction of her friend, she takes a picture of the aliens (referred to as keepers), but finds quickly that she has no memory of the event. Despite the event, and in need of money, she makes an appointment to sell her eggs, only for the keepers to shape shift from the doctors operating on her. It is only then that our hero, Caine Wise (played as a half-dog super soldier with flying boots by Channing Tatum) flies in to rescue Jupiter. Wise quickly explains that their world is not alone, and in the grand scheme of the “verse” (shortened for some reason in galactic slang), is just one of many pieces of an empire. Jupiter is just a regular woman, and yet, she is important and vital to her planet. A trio of siblings (Balem, Kalique, and Titus) rule over the House of Abrasax, one of the largest empires in the universe, which has just lost its matriarchal leader. When discovering that Jupiter is a genetic match for their late mother, they vie to bring her under their control as she is now the rightful heir to Earth.

It’s going to be hard (and unfair to the film) to detail out the entire plot of this film, but the main through line is the commodity of time and how it can be produced. As quoted at the top of this post, humanity has been stuck focusing on material resources on Earth, where those in this world have learned how to prolong life. When brought to Kalique’s planet, Jupiter discovers that one dip in a pool of clear liquid gel, and Kalique has erased her age. She is younger and rejuvenated, citing the pool for finding one’s “optimal physical condition.” It is only on Titus’ planet that she discovers the true origin of the pool, which is that the liquid is harvested from human lives.

Big suprise! The Wachowskis have returned to their idea of human beings as fuel. The planet of Earth has been secretly running as a farm for this intergalactic empire. As people die, they are being used to prolong the life of the galactic elite. The idea of humans as batteries originates in their Matrix series, but feels advanced (and predictive) to a world run by the elite instead of the machines. If The Matrix was about fighting for our humanity, Jupiter Ascending argues that we need to be reminded what our humanity is. The power and wealth of a few do not outweigh the rest, even when given the opportunity to join in the riches. The familial squabbles and insecurities of those in charge affect millions without a second thought. They are just two in the grand scheme, but isn’t it lovely that love can conquer all? The Wachowskis have always been earnest and sincere filmmakers, and that (apparently) is alienating to most audiences. Jupiter’s decision to keep Earth protected is not to control it, but to free it. The world goes on anyway, and she returns to her family, her job, and her new wolf-hybrid-boyfriend. The Wachowskis express that there are evils of the world (or “verse”), but that you can control your own life and destiny. While the battle between art and commerce feels over, art can still win.

Flashing forward, this movie made no real cultural imprint. With The Matrix officially codified as one of the pillars of film history, and their sequels and Speed Racer gaining large critical followings, Jupiter Ascending is still left in the void. This film is goofy, for lack of a better word, and far too convoluted. The plotting can be messy and overstuffed, but boy does it feel like it’s made my real people. All we tend to beg for are original blockbusters and yet, they continue to fail. It’s as if shooting for the middle time and time again has taken any voice out of what makes this medium special. Look at what this movie is about and tell me any piece of this that should be “relatable” to audiences. Do you know what should be a relatable takeaway for blockbuster entertainment? The protagonist of the film is given the opportunity for eternal youth, to be the wife of a powerful man, and to become the pseudo-matriarc of the most powerful family in the galaxy, and what does she do? Rejects them all to live her own life and create her own story.